insights

Fight Inflammation and Stabilize Mast Cells Naturally

Read Time: 5 Minutes

Arthritis. Atherosclerosis. Colitis. Eczema. Psoriasis.

Q: What are two things that all of these diseases have in common?

A: Inflammation & food.

Chronic inflammation can present in many different ways, and various nutrients and phytonutrients found in food may help to support immune health and mediate the complex process of inflammation through their effects on microorganisms in the gut.

Mast Cell Activation, Histamines, and Inflammation

Mast cells, or granulated immune cells that are located at barrier sites on the body such as the skin and gastrointestinal tract,1 are known for their role in defense against pathogens (particularly bacteria), for neutralization of venom toxins, and for triggering allergic responses and anaphylaxis. Activated mast cells also recruit other innate and adaptive immune cells and can participate in tuning the immune response. They are considered the major effector cells in allergic disorders. Mast cell stabilization is also the basis for many medications that may help reduce symptoms of allergic/inflammatory conditions.

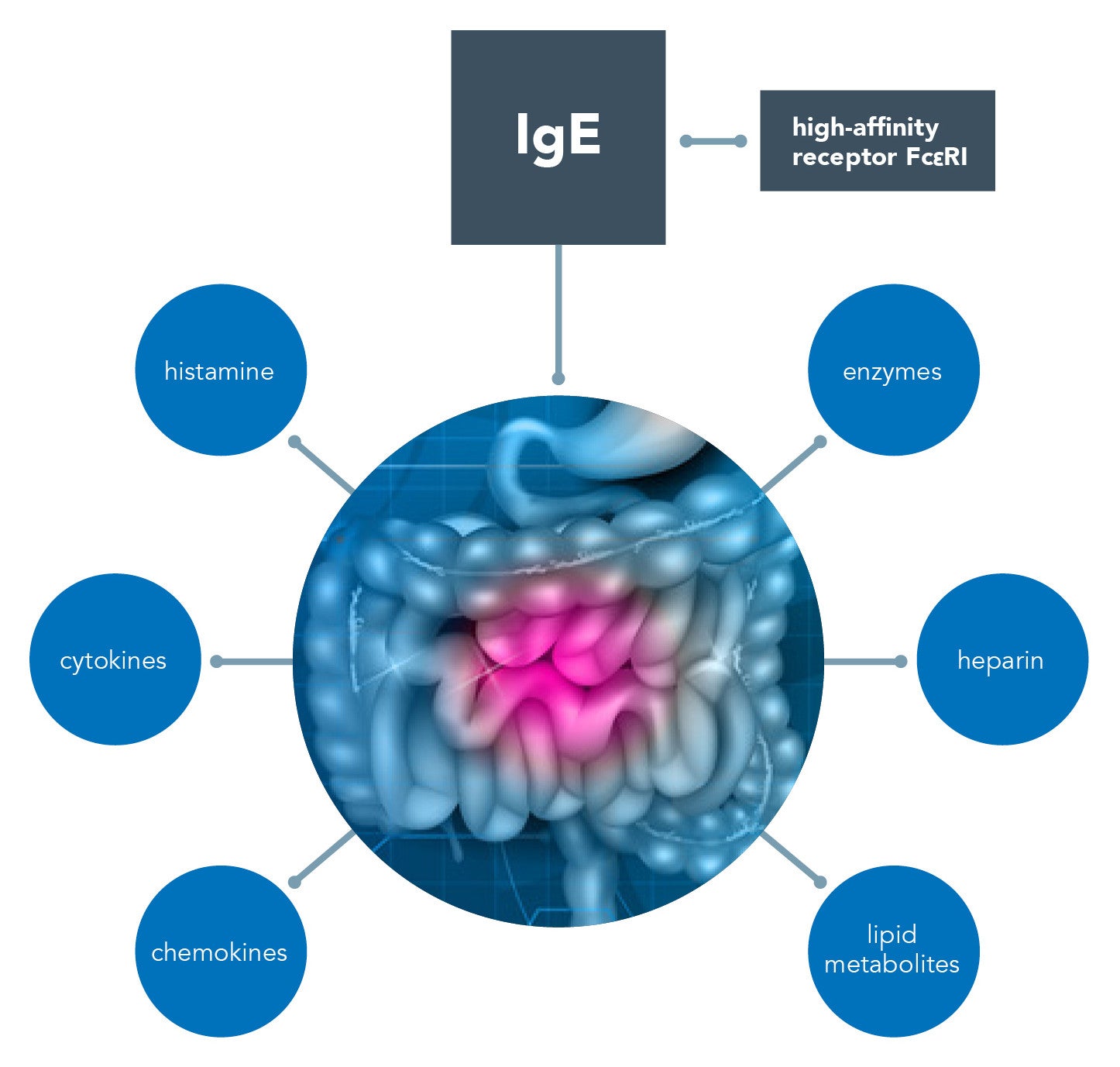

In recent years, low-grade inflammatory infiltration, often rich in mast cells, in both the small and large bowel has been observed in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).2,3 Mast cells can be activated in the gut in an IgE-dependent way via the high-affinity receptor Fc?RI, which plays a key role in allergic reactions.2 IgG, IgA, Ig-free light chains, and even complements (C3a and C5a) might also play a role via binding to the related receptors expressed on mast cells.2 When activated, mast cells release bioactive substances preformed in granules (histamine, enzymes, and heparin) and newly synthesized cytokine, chemokines, and lipid metabolites.

These mediators may participate in several disease processes beyond allergy and IBS, including functional dyspepsia, inflammatory bowel disease, and intestinal infections.4,5

Biochemical and nutritional inadequacies contribute to a dysfunctional immune response. Diamine oxidase (DAO) is an enzyme responsible for breaking down histamine. Low levels of DAO can cause histamine levels to rise and potentially lead to histamine sensitivity, chronic inflammation, or idiopathic mast cell activation syndrome—a condition in which the patient experiences repeated episodes of the symptoms of anaphylaxis, including allergic symptoms such as hives, swelling, low blood pressure, difficulty breathing, and severe diarrhea.6 High levels of mast cell mediators are released during those episodes.

Histamine-Reduced Diets & Vitamin D

Some patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders have also been diagnosed as histamine intolerant, based on low DAO values, and have reported improved symptoms after following a histamine-reduced diet.7 In a 2019 study, a significant increase of serum DAO levels was found in patients with strict and even occasional low-histamine diet compliance.7 A 2022 retrospective cohort study (n=146) also found that treatment with a low-histamine diet and/or DAO supplementation may be effective for reducing the severity of symptoms associated with histamine intolerance.8 In this specific study, patients with DAO values between 3 and 10 U/ml showed the best response to treatment.8

Research also suggests that patients with urticaria, a common skin condition that can be caused by a release of mediators such as histamine, have also shown improvement on a histamine-free diet.9 Study participants restricted foods with high histamine levels for four weeks, including foods such as tuna, mackerel, pork, and spinach, as well as fermented foods such as sauerkraut, yogurt, cheese, wine, and beer; there were significant clinical improvements in urticaria severity, and plasma histamine levels were significantly reduced after the histamine-free diet.9 In 2018, a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study suggested that DAO may be involved in the pathogenic cascade of chronic spontaneous urticarial and migraine, and that DAO supplementation could be effective for symptom relief in patients with low DAO levels in serum.10

A 2017 in vitro study found that vitamin D may be required to maintain the stability of mast cells and suggested that a deficiency of vitamin D may result in mast cell activation.11 Vitamin D’s influence on the immune response, its relationship with mast cell activation, and the potential link between vitamin deficiency and allergic diseases continues to be studied.12

Anti-Inflammatory Foods May Support Immune Health

Rather than focusing entirely on removing foods, functional medicine also seeks to enhance nutrient consumption to support immune health. What foods might fight inflammation and stabilize mast cells naturally? The following list is a selection of foods that may possess anti-inflammatory properties. Please note that some of this research is considered preliminary and/or reflected in animal studies only. More review on the topic is needed as studies vary widely in methodology.

Onions (including the spring onion) are an important prebiotic food. Quercetin (found in onions) is known for its antioxidant activity in radical scavenging and anti-allergic properties characterized by stimulation of immune system, antiviral activity, inhibition of histamine release, a decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines, leukotrienes creation, and suppression of interleukin IL-4 production.13 One study suggests that quercetin is a promising candidate as an effective mast cell inhibitor for allergic and inflammatory diseases.14 In two pilot open-label clinical trials, quercetin significantly decreased contact dermatitis and photosensitivity, skin conditions that do not respond to conventional treatment.14

Moringa is a “super-food” that has found its way onto health food shelves. It is so nutrient dense that it has historically been used to treat malnutrition. The results of a 2016 study, in vitro and in vivo, strongly suggest the beneficial effects of moringa on atopic dermatitis via the regulation of inflammatory responses.15

Chamomile is typically consumed as a tea. Fresh flowers are frequently available and are preferable to dried. One study suggests that, in mast cell–mediated allergic models, chamomile acted in a dose-dependent manner to inhibit histamine release from mast cells.16

Nettle is typically consumed as a tea. However, the results of a 2016 mouse study suggested that an herbal gel containing Urtica dioica had pain relieving and anti-edema effects without irritating the skin.17

Galangal is also called “Thai ginger” and is readily available at Asian grocers. Research using in vitro and in vivo models suggests that a compound of galangal, called galangin, may downregulate mast cell–derived allergic inflammatory reactions by blocking histamine release and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and may be a beneficial anti-allergic inflammatory agent.18

Turmeric has powerful anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Curcumin, an active component of turmeric, may possess anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities. A 2010 study suggests that nonspecific and specific mast cell–dependent allergic reactions may be significantly inhibited by curcumin.19

Peaches, a 2013 study suggests, inhibit mast cell–derived allergic inflammation.20 The inhibitory effect of peaches on pro-inflammatory cytokines was nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB dependent.20

Brazil nuts have an extraordinary selenium content. The trace mineral selenium is an antioxidant, and a single Brazil nut can provide more than twice the recommended dietary allowance of selenium. A 2013 study showed that selenium-treated mast cells revealed significant decrease in concentration of histamine and prostaglandin D2 and ?-hexosaminidase.21 In addition, a slight reduction of histamine release by the selenium-treated cells was observed, based on the study’s intracellular and extracellular assessments. The study demonstrated the potentially beneficial effects of supplemental selenium in attenuating clinical manifestations of allergy and asthma.21

Fiber – Consistent with the reported health benefits on other immune cells, studies suggest that dietary fiber (especially polysaccharides and oligosaccharides) and metabolites can regulate mast cell function. Mast cell function may be susceptible to the immunoregulatory effects of dietary fiber and butyrate.22

Personalized nutritional intervention strategies are just one functional medicine tool used to combat chronic inflammation and support a patient’s immune health. Gain additional evaluation insights and tools to fight inflammation and stabilize mast cells at the Annual International Conference (AIC).

Related Articles

References

- West PW, Bulfone-Paus S. Mast cell tissue heterogeneity and specificity of immune cell recruitment. Front Immunol. 2022;13:932090. doi:3389/fimmu.2022.932090

- Zhang L, Song J, Hou X. Mast cells and irritable bowel syndrome: from the bench to the bedside. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22(2):181-192. doi:5056/jnm15137

- Krammer L, Sowa AS, Lorentz A. Mast cells in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2019;28(4):463-472. doi:15403/jgld-229

- Wilder-Smith CH, Drewes AM, Materna A, Olesen SS. Symptoms of mast cell activation syndrome in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(11):1322-1325. doi:1080/00365521.2019.1686059

- Shah A, Fairlie T, Brown G, et al. Duodenal eosinophils and mast cells in functional dyspepsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(10):2229-2242.e29. doi:1016/j.cgh.2022.01.014

- Giannetti A, Filice E, Caffarelli C, Ricci G, Pession A. Mast cell activation disorders. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(2):124. doi:3390/medicina57020124

- Lackner S, Malcher V, Enko D, Mangge H, Holasek SJ, Schnedl WJ. Histamine-reduced diet and increase of serum diamine oxidase correlating to diet compliance in histamine intolerance. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73(1):102-104. doi:1038/s41430-018-0260-5

- Cucca V, Ramirez GA, Pignatti P, et al. Basal serum diamine oxidase levels as a biomarker of histamine intolerance: a retrospective cohort study. Nutrients. 2022;14(7):1513. doi:3390/nu14071513

- Son JH, Chung BY, Kim HO, Park CW. A histamine-free diet is helpful for treatment of adult patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30(2):164-172. doi:5021/ad.2018.30.2.164

- Yacoub MR, Ramirez GA, Berti A, et al. Diamine oxidase supplementation in chronic spontaneous urticarial: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2018;176(3-4):268-271. doi:1159/000488142

- Liu ZQ, Li XX, Qiu SQ, et al. Vitamin D contributes to mast cell stabilization. Allergy. 2017;72(8):1184-1192. doi:1111/all.13110

- Murdaca G, Allegra A, Tonacci A, Musolino C, Ricciardi L, Gangemi S. Mast cells and vitamin D status: a clinical and biological link in the onset of allergy and bone diseases. Biomedicines. 2022;10(8):1877. doi:3390/biomedicines10081877

- Mlcek J, Jurikova T, Skrovankova S, Sochor J. Quercetin and its anti-allergic immune response. Molecules. 2016;21(5):623. doi:3390/molecules21050623

- Weng Z, Zhang B, Asadi S, et al. Quercetin is more effective than cromolyn in blocking human mast cell cytokine release and inhibits contact dermatitis and photosensitivity in humans. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33805. doi:1371/journal.pone.0033805

- Choi EJ, Debnath T, Tang Y, Ryu YB, Moon SH, Kim EK. Topical application of Moringa oleifera leaf extract ameliorates experimentally induced atopic dermatitis by the regulation of Th1/Th2/Th17 balance. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;84:870-877. doi:1016/j.biopha.2016.09.085

- Chandrashekhar VM, Halagali KS, Nidavani RB, et al. Anti-allergic activity of German chamomile (Matricaria recutita) in mast cell mediated allergy model. J Ethnopharm. 2011;137(1):336-340. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.029

- Liao JC, Wei ZX, Ma ZP, Zhao C, Cai DZ. Evaluation of a root extract gel from Urtica dioica (Urticaceae) as analgesic and anti-inflammatory therapy in rheumatoid arthritis in mice. Trop J Pharm Res. 2016;15(4):781-785. doi:4314/tjpr.v15i4.16

- Kim HH, Bae Y, Kim SH. Galangin attenuates mast cell-mediated allergic inflammation. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;57:209-216. doi:1016/j.fct.2013.03.015

- Choi YH, Yan GH, Chai OH, Song CH. Inhibitory effects of curcumin on passive cutaneous anaphylactoid response and compound 48/80-induced mast cell activation. Anat Cell Biol. 2010;43(1):36-43. doi:5115/acb.2010.43.1.36

- Kim GJ, Choi HG, Kim JH, Kim SH, Kim JA, Lee SH. Anti-allergic inflammatory effects of cyanogenic and pheolic glycosides from the seed of Prunus persica. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8(12):1739-1740. doi:1177/1934578X1300801221

- Safaralizadeh R, Nourizadeh M, Zare A, Kardar GA, Pourpak Z. Influence of selenium on mast cell mediator release. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2013;154(2):299-303. doi:1007/s12011-013-9712-x

- Folkerts J, Stadhouders R, Redegeld FA, et al. Effect of dietary fiber and metabolites on mast cell activation and mast cell-associated diseases. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1067. doi:3389/fimmu.2018.01067